|

ColeJ@MerebrookLLC.com (573) 777-3564

|

Reading Land Descriptions

|

Property descriptions are found in many places and documents. They are a necessary part of every deed, right-of-way, written easement and other types of conveyance of property rights. They define the limits of what is being conveyed, saying where you have rights (and obligations) over real property. There are numerous variations of descriptions, ranging from the very simple to the extremely complicated. While the more common and basic descriptions can be followed with a little basic education, it takes years of education and experience to understand the details of the more complex descriptions. Here I will try to describe how to follow the more common and easily understood descriptions.

An interesting historical note is that in the U.S., Many school systems used to teach basic land surveying and description reading as part of the public education curriculum. Measuring and measurement calculations were taught as part of math lessons, with deed reading as part of both reading and math lessons. |

Disclaimer Let me begin with the statement that I am NOT a lawyer, attorney or other legal professional. While technically only a judge can determine where a boundary should go, and land surveyors are the only people legally authorized to place that information on the ground according to a Florida Supreme Court decision, part of being a land surveyor is knowing the law well enough to make a judgement of where a properly adjudicated boundary would be placed on the ground. Keep in mind that many court decisions are appealed several times before a properly adjudicated decision is reached, in part because there are relatively few court cases and, therefore, few lawyers or judges are familiar with the details of land boundary law.

While many legal principles are consistent throughout the U.S., the laws change depending on your jurisdiction and when it comes to land surveying, details really do matter. When in doubt, consult a knowledgeable attorney. |

Which North?

|

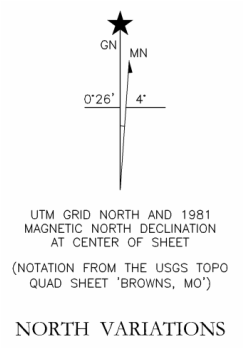

A common point of confusion in surveying is the term “north”. When “north is mentioned, surveyors immediately ask which north? There are many definitions of north and those definitions may or may not mathematically relate to other definitions. Unless north is clearly defined, assume that north is probably and generally in a northerly direction. A quick review of some of the following definitions of “north” will help you to understand the confusion and avoid some of the possible pitfalls. These are only a few of definitions available.

“True” north – True North is a general term. True according to whom? “Northerly” North – This is the north that is commonly used when a general orientation to the world is needed. I have seen it vary by as much as 45° from geodetic north. Magnetic North – Although magnetic north is simple and convenient, it can be very troublesome, because magnetic north changes over time. In central Missouri, magnetic north has varied from +8° to -2°, based on what I have seen in the records, so far. We are currently at +2°, based on personal observations. Magnetic north can also be affected by local attractions. There are many places in the world where north shifts locally, based on nearby magnetic attractors, such as iron deposits. The first time that the south line of the state of Missouri was run on the ground, the survey party, led by Joseph C. Brown, discovered that previously unknown local attractors caused the surveyed line to be off by several miles. When the error was discovered, Mr. Brown re-calculated his position from celestial observations (measuring angles to the sun and stars) and returned to where he thought he was. The mismarked line was correctly marked years later by another surveyor. Geodetic North – Geodetic North is what most people think north is. It is the axis of rotation of Planet Earth. While this sounds simple, the problem is that this changes over time. Volcanic eruptions, meteor strikes, and building huge dams all affect this rotation. Also, there is a small, cyclical wobble to the rotation of the planet, varying over cycles ranging up to several years long. State Plane North – State plane north is commonly used with GPS observations and is used as a simplified version of north for a grid system of coordinates. In a state plane coordinate system, the centerline of the SPC zone is approximately geodetic north, but since the world is not flat, the farther you go east or west from that centerline, the more state plane north varies from geodetic north. |

Azimuths - Which Way?

|

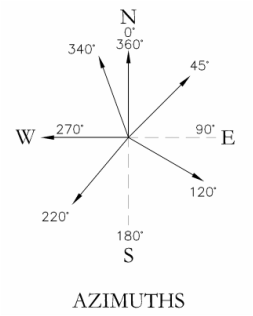

While distances are usually easy to understand because they are in either feet and inches or feet and tenths of feet, bearings can take a little more thought. A simple way to measure angles uses the same system you likely used in geometry class in school. North is set as 0° / 360°. All angles are then measured from north. A word of warning though, occasionally azimuth can be defined as 0° / 360° at some other reference, such as magnetic or true south.

|

Bearings - Which Way?

|

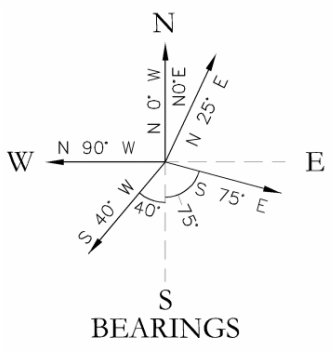

The more common method used in land surveys and property descriptions uses quadrants. The quadrants are northeast, southeast, southwest and northwest. For an example of N25°E, face north, then turn 25 degrees to the east and go that direction. If your bearing is S40°W, face south and turn 40 degrees to the west. The system is simple, it just takes a little practice to get comfortable with it.

|

Metes and Bounds

|

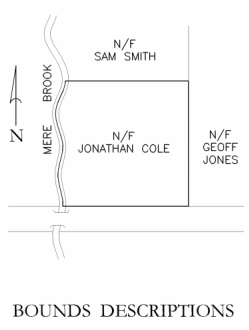

Metes and bounds descriptions are the most common type and are composed of two basic parts, the metes and the bounds. The bounds part is the easier part to understand. A pure bounds description only by what (or who) is next to them. A bounds description may read something like this:

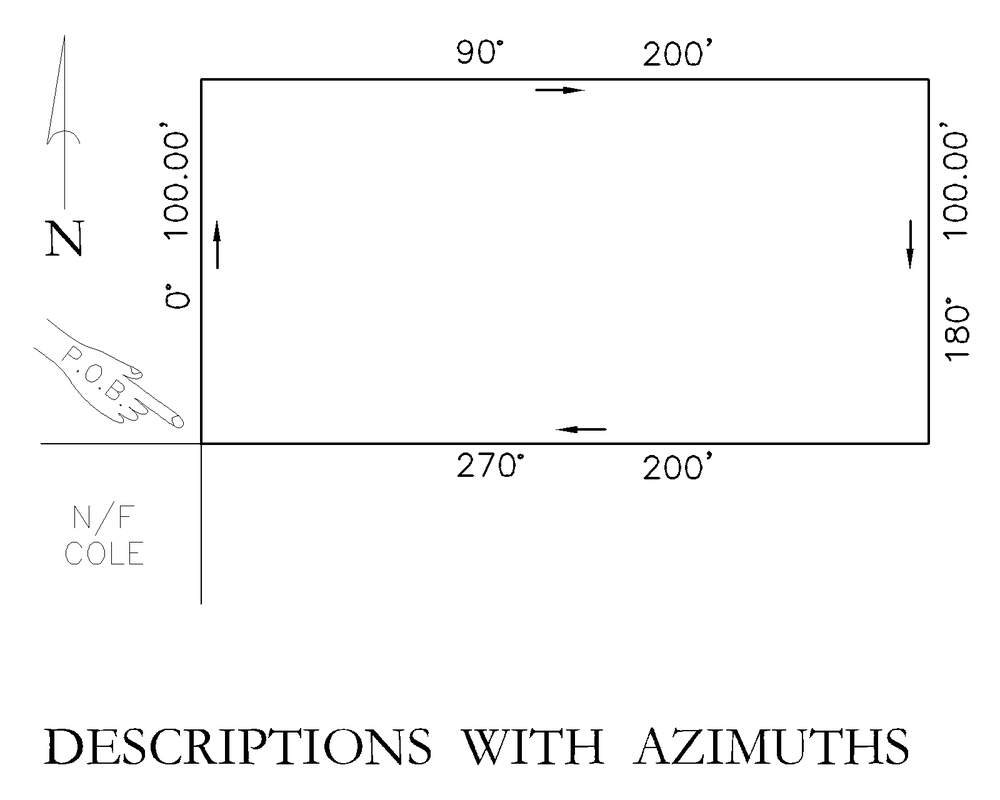

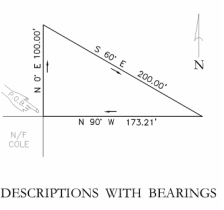

All the lands of Jonathan Cole, bounded on the north by the lands of Sam Smith, on the east by the lands of Geoff Jones, on the south by Highway 67 and on the west by Mere Brook, all in My County, Our State. The way to read this is simple. Wherever those adjoiners (neighbors whose property touches yours) property line is, that is where your line is. In order to know where your property line is, you have to survey the property of your neighbors. Metes (measured) descriptions introduce some basic math to describe the property description. A pure metes description based on azimuths is simple. A simple metes description may read something like this: A parcel of land beginning at the northeast corner of Cole; thence 0° a distance of 100 feet, thence 90° a distance of 200 feet; thence 180° a distance of 100 feet; thence 270° a distance of 200 feet to the point of beginning. The way to read this is to first find where the northeast corner of Brown is, then start around the property boundary. Azimuth angles read the same as if you are using a compass with 0° assumed as “north”. So, in this case, go north (0°) a distance of 100 feet; then turn to the right to an azimuth of 90° (east) and go 200 feet; then turn right again to an azimuth of 180° (south) and go a distance of 100 feet; then turn right again to an azimuth of 270° (west) and go a distance of 200 feet to where you started. The result is a rectangle 100’ x 200’, touching the property of Brown at its southwest corner. The more common metes description uses a modified version of the angles. These angles follow the pattern of North or South / angle / East or West. An example is N5°E. To follow this angle you turn and face north, turn five degrees towards the east and then go the specified distance. A simple example may read something like this: A parcel of land beginning at the northeast corner of Cole; thence N0°E a distance of 100 feet; thence S60°E a distance of 173.21 feet; thence N90°W a distance of 200 feet to the point of beginning. The way to read this is to find where the northeast corner of Cole is, then face north and turn 0° to the east (still north in this case) and go 100 feet; then face south and turn 60° to the east (left in this case) and go 173.21 feet; then face north and turn 90° to the west (due west in this case) and go a distance of 200 feet to where you began. Most commonly, descriptions combine metes and bounds together, specifying which way to turn, how far to go, and when to stop based on the distance and/or the bounds call, such as, go S45°W a distance of 365 feet to the east line of Merebrook Subdivision. If there is a conflict between the distance and bounds call, such as if you find that the distance measures as 400 feet, a lawyer or land surveyor will need to make the determination of which to hold, based on a long list of legal principles designed to protect the rights of all parties involved. As you can see, this is a very flexible system of land description which has been used for centuries, but it has some problems. How do you know where that pesky starting point is? What happens when the name of the bounding adjoiners (neighbors) change? How do you know that your property is not overlapping the land of someone else? While most of those questions can be answered by some research by a land surveyor, title company or attorney. The vast areas of the Louisiana Purchase caused a need for the rapid dividing and sale of lands by the U.S. government, resulting in the U.S. Public Land Survey System (US PLSS). |

Public Land Survey System - PLSS

|

The vast areas of the Louisiana Purchase caused a need for the rapid dividing and sale of lands by the U.S. government, resulting in the U.S. Public Land Survey System (US PLSS).

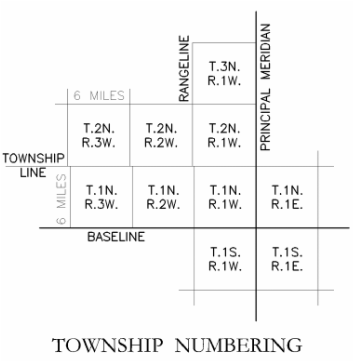

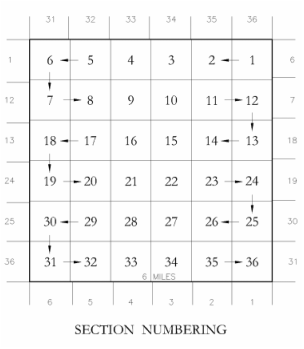

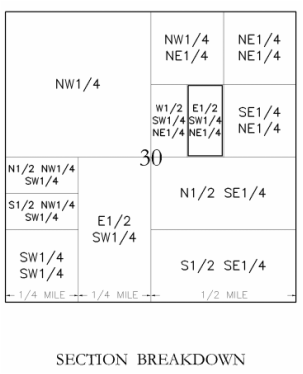

The U.S. Public Land Survey System seeks to lay a square grid of property lines over a round world and to allow for the inevitable errors as it goes. It starts with a north-south reference line called a Principal Meridian (P.M.) and an east-west reference line called a Base Line (or baseline). These lines are the starting place for every other line in the system of land descriptions. Missouri’s principle meridian (the 5th Principal Meridian) and its baseline were run in 1815. The starting point where these two lines intersect is in eastern Arkansas. Townships are the major ‘building blocks’ of the PLSS system. They are nominally 6 miles square, but because of surveying a square system onto a round world and an inability for anyone to measure anything perfectly, the townships are, in reality, shorter or longer than 6 miles on a side. Townships are placed in a grid pattern, measuring north from the baseline (the east-west reference line) and west from the Principal Meridian (a north-south rangeline). A general point of reference is that Columbia, Missouri, is in Township 48 North, Range 13 West of the 5th Principal Meridian. There are many irregular townships that look radically different from the standard township and in each of these, the original measuring errors were placed along the north and west lines of the township. (see diagram) Standard Townships are each broken down into thirty-six Sections, with each Section being one mile on each side and containing 640 acres. Sections west of Ohio are all numbered in the same order, beginning with one in the northeast corner, continuing in order to number six in the northwest corner of the Township. The next section, number seven, is due south of section six, with the numbers now increasing as you go east. This zig-zag pattern is continued throughout the rest of the Township, ending with number thirty-six in the southeast corner of the Township. (see diagram) Sections are then broken down into parts, containing quarters, halves, sixteenths, etc. A half of a section (320 acres) is created by drawing a line from the mid-point of a section line to the midpoint of the opposite section line. A quarter of a section (160 acres) is created by drawing both the north-south half-section line and the east-west half-section line, breaking the section into four parts. Each part of a section can then be broken down using the same method, giving you such things as the east half of the southwest quarter of the northeast quarter of a section. Read It Backwards Because of the order that these descriptions are written, it is often useful to read the breakdown of a section in reverse order. So, let us imagine that your description reads: The East Half of the Southwest Quarter of the Southeast Quarter of the Northeast Quarter of Section 30, Township 50 North, Range 12 West. Using USGS topographic maps, plat books, or some other reference, you find that you are in the township that has its southwest corner in Finger Lakes Park, north of Columbia, Missouri. You read that you are in Section 30 (640 acres), which is on the west line of the township and one mile from its southern edge, putting you near the north end of the campgrounds in the park. You then break the section into quarters, highlighting the northeast quarter (160 acres). Then break that quarter section down into quarters again, highlighting its southwest quarter (40 acres). Finally, break that part into halves, highlighting the east half. That last part marked is the land described in the description (80 acres). (see diagram) Keep in mind that the nominal acreage of that description is probably not the actual acreage, but it will give you a pretty good idea of about how big the parcel is. |

Section Corners

|

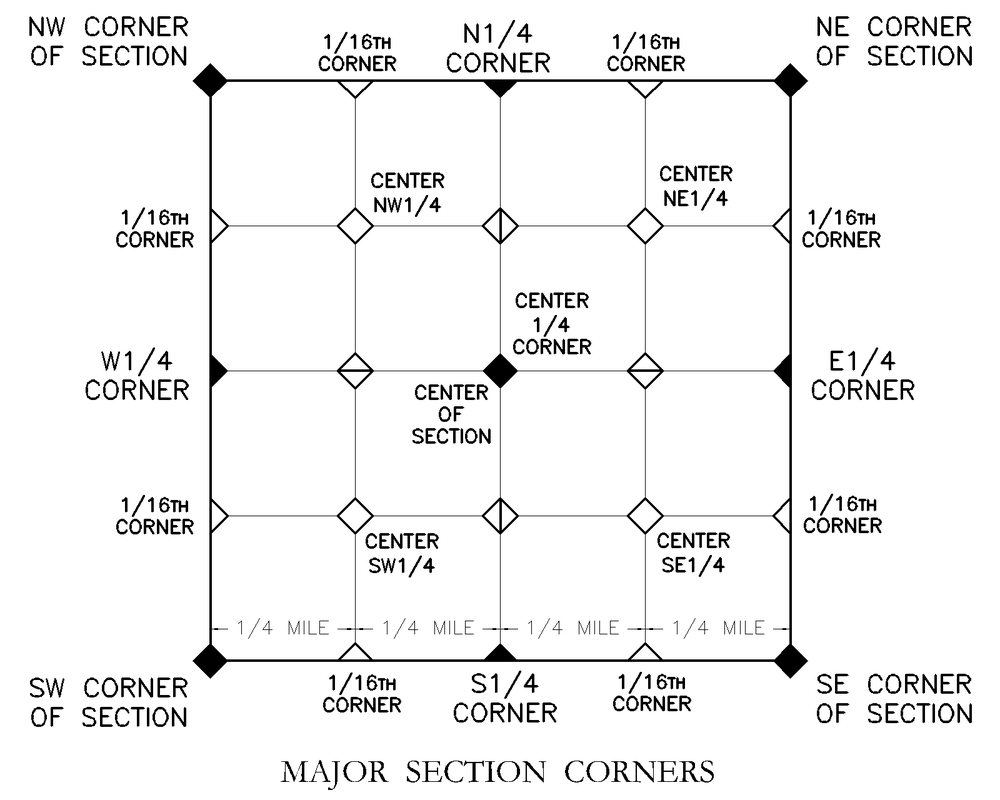

When a description is tied to the PLSS, it is common to refer to particular corners as the point of beginning or as a tie point along the way. Sometimes the way they are described follows the standard section breakdown instead of common English. Several examples of this method are shown in the diagram ‘Major Section Corners’.

|

Combining Descriptions

It is common for descriptions to contain elements of metes, bounds and PLSS breakdowns. A description may begin at a reference point (e.g. a Point of Commencement or Point of Beginning) at the quarter corner of a section, follow along a quarter section line to the edge of the subject parcel (i.e. Point of Beginning or True Point of Beginning), and then go around the parcel using a metes and bounds description.

A variation to these two kinds of descriptions is describing a lot in a subdivision. The subdivision plat (or map or drawing) draws pictorially (maps) and describes with words (description) individual lots or parcels within its outer boundaries. This larger parcel is then broken down into smaller lots and tracts, which are then sold off. A simple description of this type might read:

Lot 11, Block 3 of Cole Subdivision, Boone County, Missouri.

It looks awfully short, but this description packs quite a punch. It says which county and state the land is in. It also refers to a subdivision which has been recorded in the Boone County Recorder’s Office. This allows anyone to go look up this subdivision and see what the lot looks like. Pulling up a copy of the subdivision, you see that it is broken down into groups of lots, called blocks and that these blocks are then broken down into smaller parcels called lots. By finding Lot 11 in Block 3, you can see exactly where your lot is. A nice things about doing descriptions this way, instead of using a metes and bounds style, is that it is much harder to make a mistake in the description when you copy it from one document to another. Referring everyone to a single document at the recorder’s office, the parcel is thoroughly described, because every dimension, bearing, description, line and marking on that drawing is now considered to be part of your ‘simple’ description, making it much easier to find your boundaries in the future.

A variation to these two kinds of descriptions is describing a lot in a subdivision. The subdivision plat (or map or drawing) draws pictorially (maps) and describes with words (description) individual lots or parcels within its outer boundaries. This larger parcel is then broken down into smaller lots and tracts, which are then sold off. A simple description of this type might read:

Lot 11, Block 3 of Cole Subdivision, Boone County, Missouri.

It looks awfully short, but this description packs quite a punch. It says which county and state the land is in. It also refers to a subdivision which has been recorded in the Boone County Recorder’s Office. This allows anyone to go look up this subdivision and see what the lot looks like. Pulling up a copy of the subdivision, you see that it is broken down into groups of lots, called blocks and that these blocks are then broken down into smaller parcels called lots. By finding Lot 11 in Block 3, you can see exactly where your lot is. A nice things about doing descriptions this way, instead of using a metes and bounds style, is that it is much harder to make a mistake in the description when you copy it from one document to another. Referring everyone to a single document at the recorder’s office, the parcel is thoroughly described, because every dimension, bearing, description, line and marking on that drawing is now considered to be part of your ‘simple’ description, making it much easier to find your boundaries in the future.

Areas

A quick note about areas. Even if they are carefully and accurately calculated (as they should be) in most descriptions, areas are only a reference. They are used for comparisons and often for tax purposes, but they rarely define where the parcel’s boundary lines are. So, Lot 1, containing 1.00 acres, really means that you own Lot 1 and that it contains 1.00 acres as it was calculated, but this number may vary based on any number of good reasons. As a practical matter, 0.001 acre equals about 6.6 feet by 6.6 feet.